This is the penultimate installment in a series on Wisconsin’s boundaries. Oddsconsin 50 examined the Illinois boundary, while Oddsconsin 51 and Oddsconsin 52 looked at the Minnesota boundary. This post focuses on Wisconsin’s boundary with Michigan, a topic that will conclude next week in Oddsconsin 54.

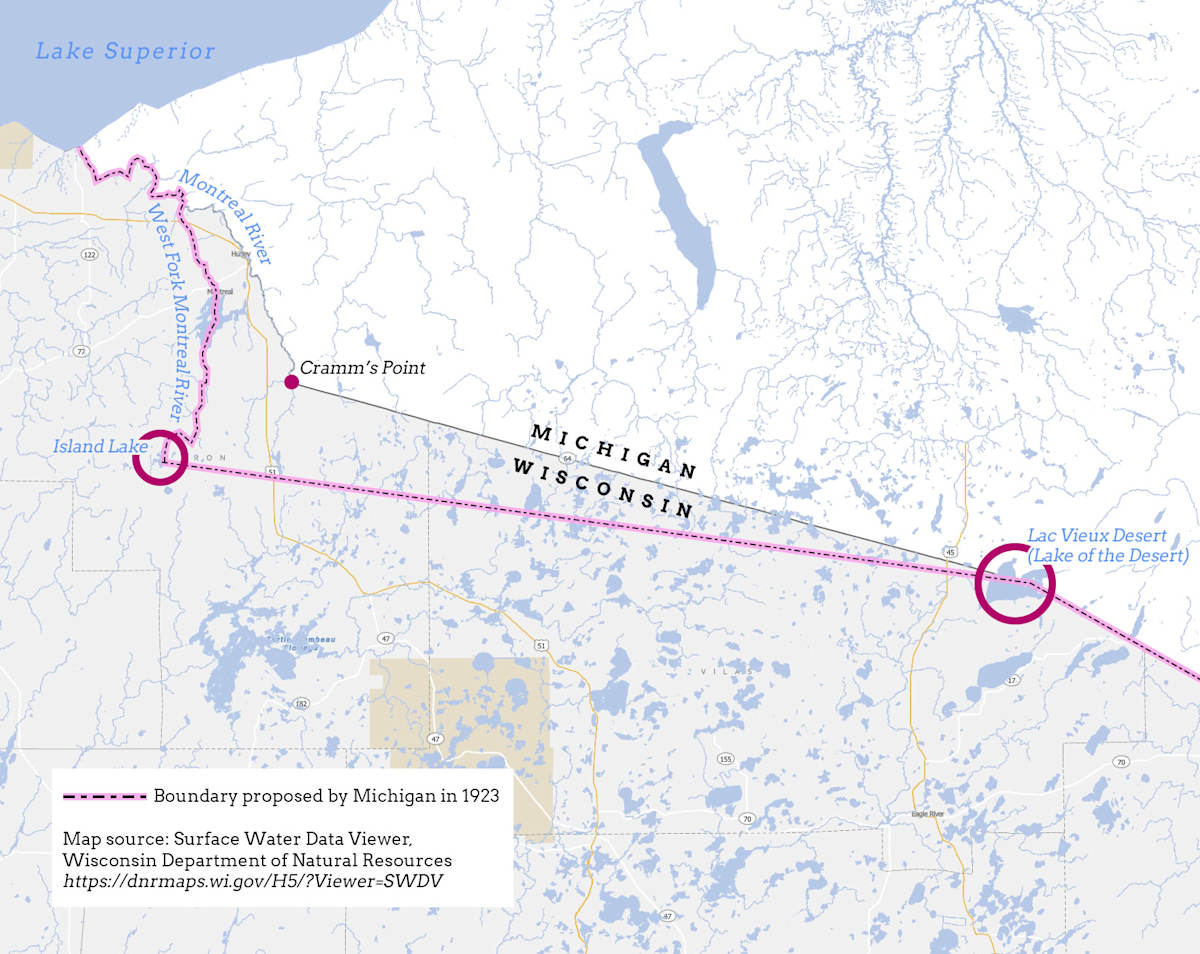

The map that accompanies this post shows the boundary between Wisconsin and Michigan in different shades of gray. This depiction is in agreement with Article II of the Wisconsin Constitution [1] where the boundary is described as running from the

mouth of the Menominee river; thence up the channel of the said river to the Brule river; thence up said last-mentioned river to Lake Brule; thence along the southern shore of Lake Brule in a direct line to the center of the channel between Middle and South Islands, in the Lake of the Desert; thence in a direct line to the head waters of the Montreal river, as marked upon the survey made by Captain Cramm; thence down the main channel of the Montreal river to the middle of Lake Superior.

Captain Cramm is the second individual named in Article II, the other being Joseph Nicollet (see Oddsconsin 51). Who was Captain Cramm and what did he do to earn a mention in the state’s founding document?

Captain Thomas Cramm (usually spelled Cram, 1804-1883) was an engineer in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. Cram was charged with surveying the boundary between Wisconsin and Michigan following the separation of Wisconsin Territory from Michigan Territory in 1836 and the creation of the state of Michigan in 1837.

The boundary separates Wisconsin from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which was granted to Michigan as a concession following the so-called Toledo War, in which Michigan and Ohio both claimed a prized strip of land on Lake Erie around the current city and port of Toledo, Ohio.

The boundary between Wisconsin Territory and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan was described in 1836 as following the

mouth of the Menomonie [Note: now spelled Menominee] river; thence through the middle of the main channel of said river to the Brule river, to that head of said river nearest to the Lake of the Desert; thence in a direct line to the middle of said lake; thence through the middle of the main channel of the Montreal river, to its mouth.

This description is a bit different from the one in the constitution. Both reference Lake of the Desert, but the 1836 description is based on the incorrect belief that Lake of the Desert drained westward through the Montreal River into Lake Superior. That is, the boundary line is described as running from Lake of the Desert directly into the main channel of the Montreal River. [2]

During his 1840 expedition, Captain Cram found it was impossible to follow the 1836 description. First, he did not find a lake called Lake of the Desert, so he decided that Lake of the Desert was in fact Lac Vieux Desert, which had a similar name. He also discovered that the Montreal River did not drain this lake, but was an eight-day journey overland to the west. He realized the boundary description was useless and recommended using a point in Lac Vieux Desert as a turning point on a straight-line boundary connected to the Montreal River in the west. [3]

Cram’s follow-up expedition of 1841 identified the eastern branch of the Montreal River as the main channel. He made an astronomical observation at the junction of what were then known as the Balsam and Pine Rivers, which he considered the headwaters of the Montreal River. These rivers have since been renamed, such that Cram’s point today is at the confluence of the Montreal River and Laymans Creek.

The location of Cram’s point in relation to the Wisconsin-Michigan boundary is shown on the map that accompanies this post.

Cram’s information was used by Congress to modify the 1836 Michigan-Wisconsin boundary description in the 1846 Enabling Act that paved the way for Wisconsin statehood. Cram’s point on the Montreal River was specifically included in the boundary description as a precise, surveyed location. This is why it shows up in the state's constitution. [4]

A year before statehood, in 1847, the Michigan-Wisconsin boundary was surveyed and monuments were set at half-mile intervals. These were simply wooden posts, but they defined the boundary unambiguously on the ground. The survey was conducted by the Surveyor General’s Office and certified that same year.

The case seemed to be closed, but then Michigan initiated a law suit in 1923 that went all the way to the US Supreme Court. To find out why, tune in next week for Oddsconsin 54.

Want Oddsconsin delivered right to your inbox? Subscribe here.

Sources and Notes

[1] Wisconsin Constitution. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/constitution/wi_unannotated

[2] Franklin K. van Zandt, Boundaries of the United States and the Several States. Geological Survey Professional Paper 909, Washington, DC, 1976.

[3] Lawrence Martin, The Michigan-Wisconsin Boundary Case in the Supreme Court of the United States, 1923–26, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1930, pp. 105-163.

[4] Wisconsin Historical Records Survey, Origin and Legislative History of County Boundaries in Wisconsin. Madison, WI, 1942.