This is the 3rd part of a 3-part series. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

After the magnetic experiments ended, UW-Madison’s underground observatory lay dormant until 1896, when Professor Harry L. Russell was given permission by the UW Board of Regents to use it to conduct experiments on cheese curing. [1]

Russell, a native Wisconsinite, came to the University of Wisconsin in 1893 to head dairy-related bacteriological work at the Agricultural Experiment Station. In 1896, William A. Henry, Dean of the Wisconsin College of Agriculture, asked Russell and Stephen M. Babcock (another UW professor who had recently developed a test for measuring the butterfat content of milk) to work together on cheese making.

At the time, the Wisconsin cheese industry was in dire straits. Often produced by small local cheese makers with meagre facilities, the cheese was of poor quality, which affected sales nationally and internationally. Known problems included filthy dairy conditions, the use of skimmed milk, additives such as lard and linseed oil, and high-temperature curing, which melted out the fat and produced dry, cracked cheese. [2]

Russell and Babcock took a scientific approach to cheese making, looking at milk quality, sanitary conditions at dairies and, especially, cheese-curing methods. They quickly realized that high-temperature curing caused problems with flavor, aroma and shelf life. But at the time, low-temperature curing was not well understood. Russell and Babcock experimented for years, curing cheese at temperatures well below industry practice. The underground chamber at UW-Madison was one of the sites for these experiments.

Compared to warm-cured cheese, cold-cured cheese tasted better, lasted longer, yielded more cheese per pound of milk and eliminated losses from shrinkage, mold and undesirable taints introduced by bacteria. The only drawback was its longer curing time. Cold-curing remained the standard until the 1930s, when the growing use of bacteria-free pasteurized milk allowed cheese makers to elevate curing temperatures. [2]

The repurposed underground observatory helped Russell and Babcock save the Wisconsin cheese industry at a very critical time. Without them, Green Bay Packers fans might be wearing brats or cream puffs on their heads instead of cheese wedges.

After Russell and Babcock finished their cheese research, the underground chamber faded into obscurity for a time. Some accounts indicate it was used for potato and oil storage. [3] It reappears as a site for initiation ceremonies for new members of the chemistry fraternity Alpha Chi Sigma.

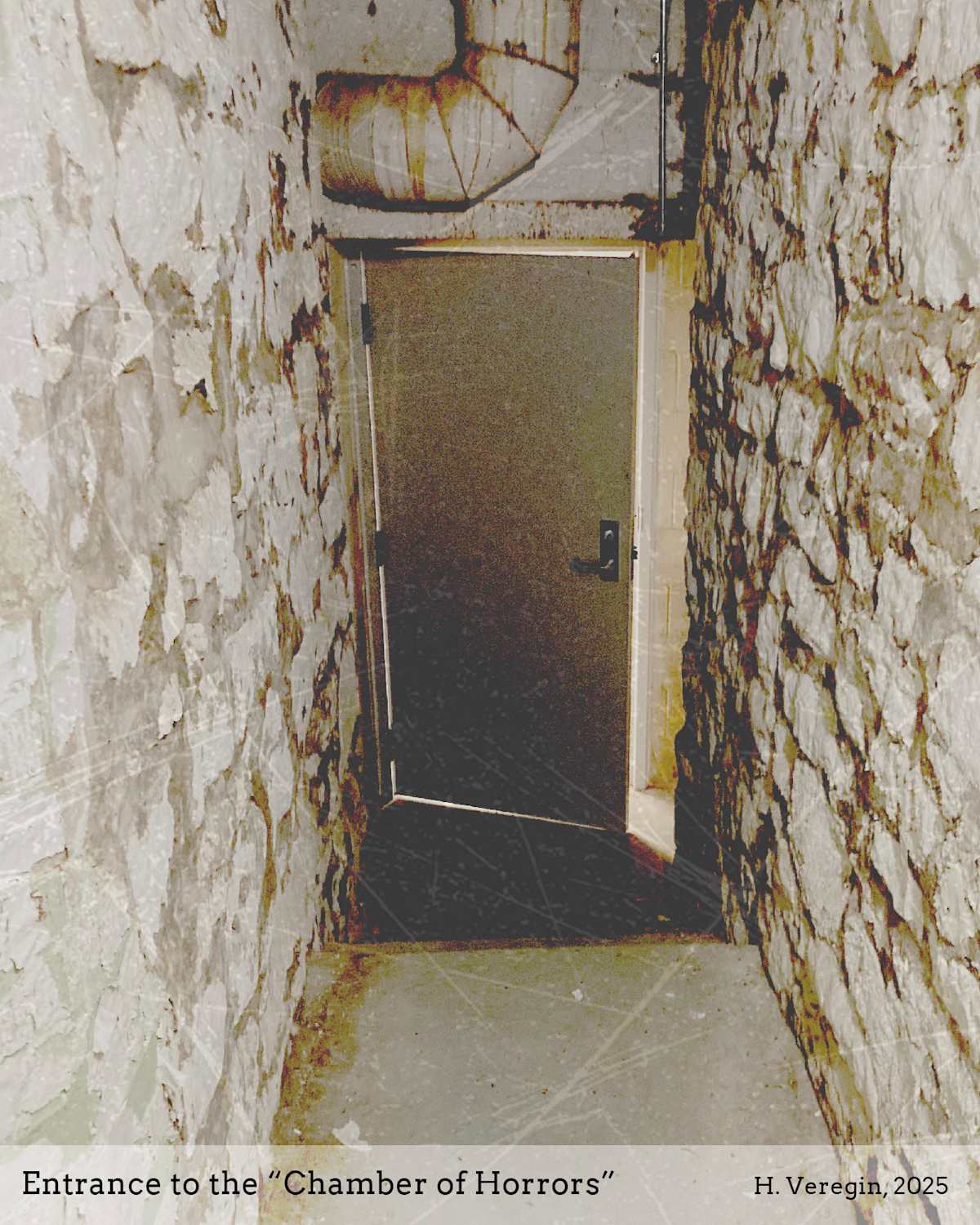

The Alpha Chi Sigma website has a fascinating first-hand account of one of these rituals in 1903. [4] The account describes the facility as an underground meteorological station on the south slope of University Hill. (Meteorology? Not quite, but after all, they were chemists, not geographers.) At the time of the initiation ritual, the “old cave” consisted of two unlighted, rough-walled rooms, long abandoned and possessing “a high degree of spookishness.”

The candidates for the initiation ritual (Brothers Lee and Wheelwright), after blindfolding themselves, were instructed to wait in the shadows of the chemistry building. Brother Lee’s account indicates that, after a long wait, his escorts appeared, further restricting his vision by pulling a knitted cap down to his nose.

After entering the underground “Chamber of Horrors,” he was forced to answer some “startling” questions that elicited “merriment among the members.” Following this cross-examination came “stunts” – picking something out of a pan of water charged with electricity and burying his hands inside putrid flesh (a piece of raw liver), while the members held “vials of disgusting odors” to his nose and made “cavernous noises.” The liver was supposed to represent the “decomposing remains of a mythological brother alchemist who had been blown to atoms in the process of his alchemical researches.” After this, Brother Lee was admitted to Alpha Chi Sigma.

That’s a lot of history for one small room obscurely buried under Bascom Hill – magnetic field observatory, cheese-curing facility, site for fraternity rituals, and (finally) home to a colony of dermestid beetles. No doubt, with enough research, many of the other old buildings on UW-Madison’s campus would reveal equally interesting histories.

Sources:

[1] Feldman, Jim, 1997, The Buildings of the University of Wisconsin https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AHR5KYLU44F7DU85

[2] Beardsley, Edward H., An Industry Revitalized: Harry Russell, Stephen Babcock, and the Cold Curing of Cheese, The Wisconsin Magazine of History , Winter, 1965-1966, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 122-137 https://www.jstor.org/stable/4634124

[3] The Dermestarium, UW Zoological Museum, UW-Madison https://uwzm.integrativebiology.wisc.edu/dermestarium/

[4] Mathews, J. H. & Kundert, Alfred, Reminiscences, Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity https://alphachisigma.org/Docs/History/ReminiscencesNEW.pdf