This is the 2nd part of a 3-part series. Read part 1 here.

UW-Madison’s dermestarium was not always full of beetles. It was built in 1876 as an observatory to conduct measurements of the earth’s magnetic field. In 1875, the US Coast Survey – a federal scientific agency – approached the University of Wisconsin about establishing the observatory. What attracted their interest was Professor John E. Davies and his work on magnetism. Davies (1839-1900) taught science at Lawrence College, his alma mater, after the Civil War. He graduated with an MD from Chicago Medical College in 1868 and came to the University of Wisconsin as a professor of natural history. [1]

The purpose of the observatory was to produce a “continuous and reliable record of the variations in the direction and intensity of the earth's magnetic force, by means of photographic self registration.” [2] Why the interest in magnetic fields? To study how the magnetic state of the earth is influenced by the position of the sun and moon, and to look at the connection between auroral displays, sunspots and magnetic variations. [3]

The US Coast Survey supplied the equipment, including magnetometers and declinometers – devices with suspended magnets that move in relation to magnetic fields. The equipment was finicky and delicate. Magnets were suspended “by a skein of one hundred fibres of silk” to minimize tension that might bias the magnetic readings. [3] One magnetometer had to be adjusted to a precision of thousands of an inch and it could take days to correctly shift its center of gravity to account for slight changes in temperature. [3]

Recordings were kept photographically on a cylinder covered in light-sensitive paper. For this reason, the room was dark, with only a few gas lamps and a stearin candle used for lighting. [3]

According to a popular account from the day,

“The darkness, which would be absolute but for the faint gleams of light escaping through the close coverings of three lamps; the silence, broken only by the ticking of two clocks, or the tread upon the paved floor; the strange character of the instruments, which he begins dimly to see – all unite to create a feeling of oppression, as though one breathed the air of some sorcerer's den.” [3]

From sorcerer’s den to a home for flesh-eating beetles!

The magnetic experiments were up and running by 1878. The work was tedious. Temperature was an issue, since magnets lose their strength as it gets hotter. The chamber was built with an outer wall surrounding a dead-air space, to keep the temperature as steady as possible. [2]

Metal was another problem. The observatory was deliberately located far from water and gas lines. It was built of brick and cement without the use of metal. There were no metallic supports or mountings. Metal cans to refill the oil lamps were not permitted. Visitors needed to give up their keys, glasses and other metal objects before entering. [3]

The US Coast Survey was known as the Survey of the Coast when it was created by President Thomas Jefferson in 1807. Its mission was to survey and chart the coastlines of the country. The agency has a long and beleaguered history. After the War of 1812, it was briefly suspended from work due to objections from the military. Congress handed the job of surveying the coasts to the US Navy and prohibited civilian surveyors from doing so. The Survey of the Coast resumed civilian operations in 1836 under its new name, the US Coast Survey. In 1878 it was renamed again, to the Coast and Geodetic Survey. [4]

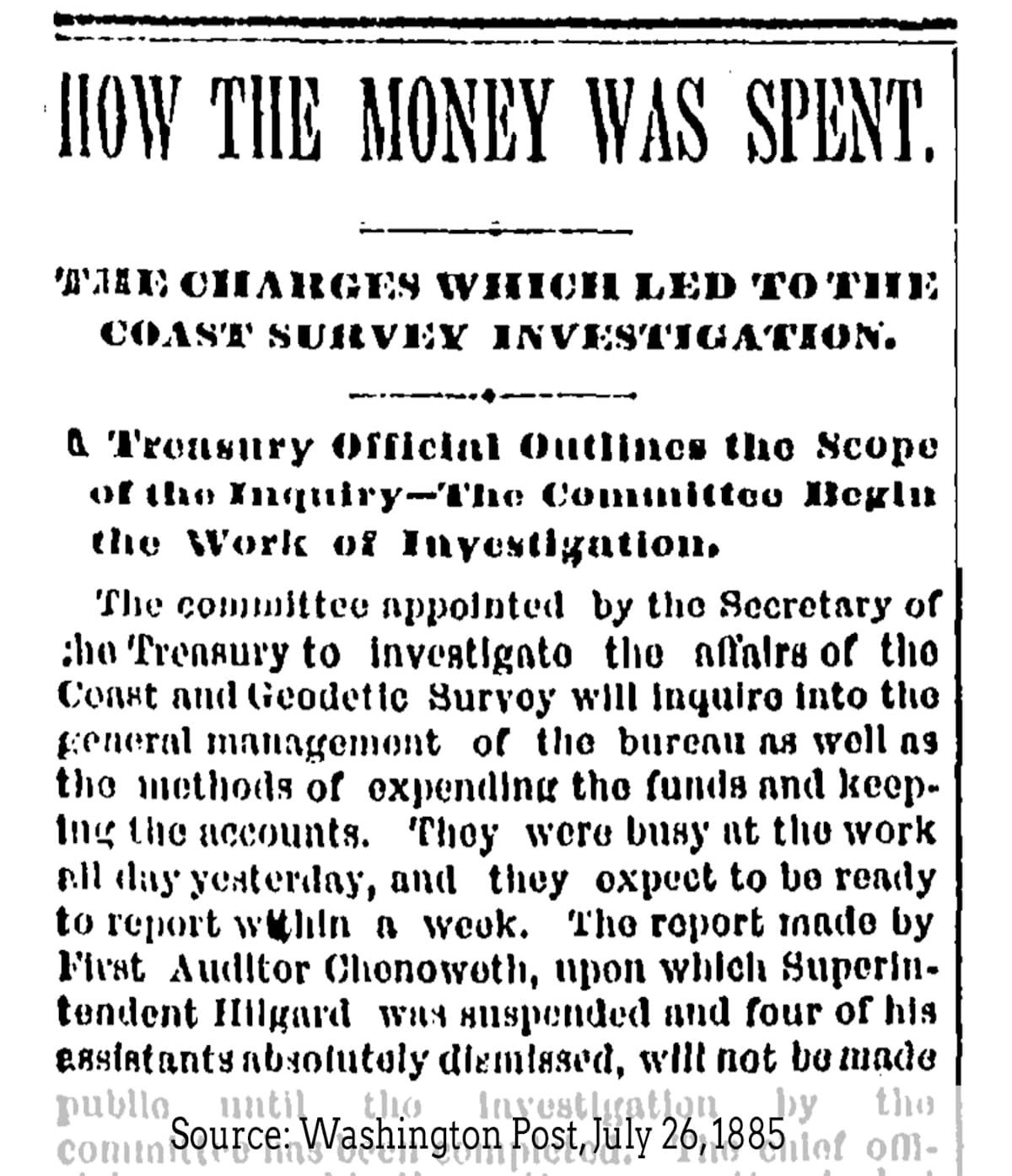

Unfortunately, the magnetic observatory operated for only a few years. What apparently killed it was a financial scandal that erupted in Washington DC in the 1880s, when the joint House/Senate Allison Commission was formed. The Commission examined the activities of the Coast and Geodetic Survey (and several other agencies) and found evidence of financial mismanagement. The Commission also raised concerns about the abstract nature of the Survey’s scientific work, questioning whether it should be funded by the government.

In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed James Q. Chenoweth (or Chenowith) – a former Confederate Army officer – to be First Auditor of the Treasury Department. Chenoweth began investigating the Coast and Geodetic Survey, quickly suspending the superintendent of the agency and appointing Frank M. Thorne of the Internal Revenue Bureau in his place. For the first time, the Coast and Geodetic Survey would be led by a superintendent who was not a scientist. [5]

Special thanks to Richard Kleinmann for making me aware of the magnetic observatory.

Next week: Cheese curing and strange fraternity rituals!

Sources:

[1] Davies, John Eugene 1839 – 1900, Wisconsin Historical Society https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS6909

[2] Feldman, Jim, 1997, The Buildings of the University of Wisconsin https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AHR5KYLU44F7DU85

[3] Davis, E. W., The Magnetic Observatory at Madison, Wisconsin, Popular Science Monthly, Volume 12, February 1878.

[4] History of the Coast Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration https://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/about/history-of-coast-survey.html

[5] Cloud, John (no date), Science on the Edge: The Story of the Coast and Geodetic Survey from 1867-1970 https://library.oarcloud.noaa.gov/docs.lib/htdocs/rescue/coastandgeodeticsurvey/science_on_the_edge/science_on_the_edge.pdf