Since 1950, the University of Wisconsin-Madison has operated a dermestarium in a small underground chamber on campus. What’s a dermestarium? The word is derived from Latin and roughly translates into “a place for eating skin.” The university’s dermestarium is home to a colony of thousands of dermestid beetles, whose job is to clean animal skeletons so that they can be preserved for study and research.

The existence of the dermestarium is hardly a secret. [1][2][3][4][5] What makes the facility unique, however, is its history, which stretches back to its construction in 1876. It’s older than almost every other building on campus, notable exceptions being North and South Halls (1851 and 1855), the La Follette Institute building (ca. 1855) and Bascom Hall (1859).

The underground chamber was not built as a dermestarium, but as an observatory to measure minute changes in the earth’s magnetic field. When that venture was curtailed due to a national financial scandal, the observatory was adapted to conduct experiments on cheese-curing methods. Later, it became the site of a strange initiation ritual for members of a student fraternity. It wasn’t until 1950 that it became home to the dermestid beetle colony.

The dermestarium is closed to the public, so to arrange a tour, I reached out to Laura Monahan, Distinguished Associate Director and Curator of Osteology at the UW Zoological Museum (UWZM). [6] The museum and dermestarium are part of the Department of Integrative Biology. The museum houses bone specimens that have been cleaned by the dermestarium’s beetle colony. UWZM has over half a million specimens, from mussel shells to hippo skulls. It also houses bird and mammal skins, as well as some specimens, like fish, preserved in liquid. The museum is a research facility. The specimens are stored in boxes like a library archive.

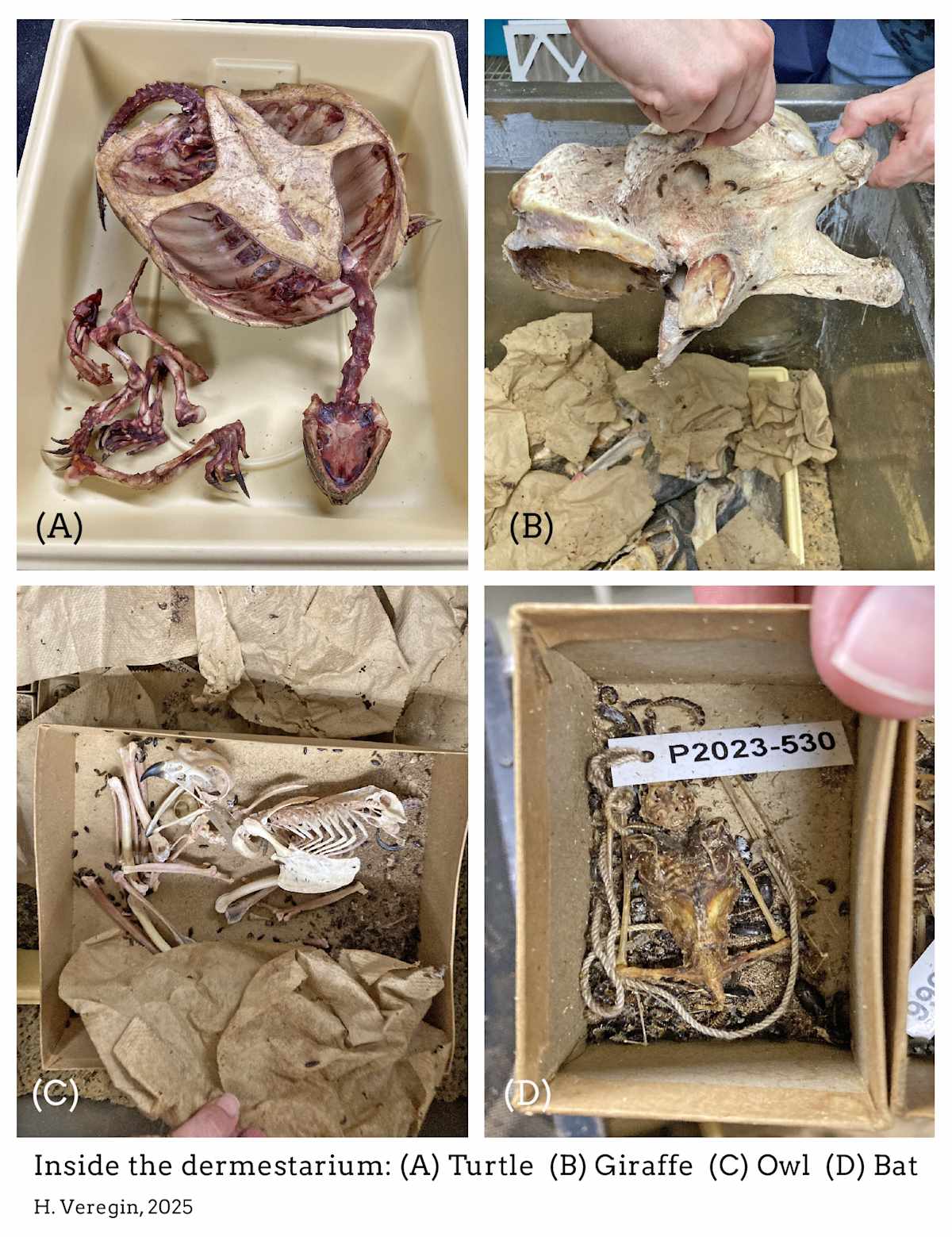

My dermestarium tour will be conducted by John Stuhler, UMZM’s Curator of Mammals and Birds, who is responsible for managing the facility. On the day of the tour, John arrives carrying a large plastic tub, which I immediately assume is full of donuts. It turns out to be the skeleton of a turtle. The flesh is gone, but the skull, backbone, claws and shell remain. I’m surprised by the length of its neck. John explains that, before the specimens come to the dermestarium, most of the soft flesh is removed manually, and then the bones are dried so that the remaining flesh takes on the consistency of jerky. After the beetles do their job, only minor cleaning is needed to make the specimens ready for UWZM.

The dermestarium is underground for a reason – it’s ideal for maintaining the correct temperature and humidity conditions for the beetles. A long stone tunnel leads to the entrance of the chamber. It feels a bit like entering a tomb. The chamber itself is small (16 by 18 feet). It’s a utilitarian workspace, nothing fancy. The brick walls are painted off-white. Metal shelves hold supplies like Borax, Clorox, boric acid, water bottles, plastic tubs and metal pans. There’s an old sink and a few trash cans. It’s reminiscent of a basement workshop in an old house. It smells a little funky, but not like rotting flesh. That’s because the animal flesh on the bones is already dry.

The bones are kept in stainless steel tanks covered with screens. Each tank has a name: Tyrannus (a genus of small birds), Tamias (rodents) and Taxidea (American badger). Biology humor? John sets down the turtle and lifts one of the screens. Inside the tank, stacks of bones are covered in damp paper and thousands of beetles scurry around. “It’s a giraffe skeleton,” says John. It’s been disarticulated and there are pieces of the animal in several different tanks. I wonder how John keeps it all together in his mind.

John sprays some water on the paper, which makes the beetles more active. Then he pulls out a piece of the giraffe skull and shows me the knobby horns. The mandible, with its massive plant-grinding molars, sits at the bottom of the tank. Also visible are what seem to be hip bones, leg bones and hoofs.

John shows me a photo of the messy process of removing the giraffe’s fleshy parts, including the large papillae that hang from its palette. It’s a bit gruesome. “You get used to it,” John says nonchalantly. Over a thousand specimens are processed in the facility each year. The giraffe was donated by a zoo. Zoos in Madison, Green Bay, Racine and Milwaukee all donate animals, as does the Humane Society and the State Hygiene Lab. The latter is a source of bats, which are donated after a rabies test is performed (if results are negative). There are several bat skeletons in the tanks. They seem very fragile. John explains that bats must be watched carefully, or the hungry beetles will eat the bones. The same goes for fish.

The beetle colony is self-replicating. It’s the same colony that’s been here for decades. John estimates that there are probably half a million beetles here. We look in a few more of the tanks. It will take six months for the beetles to clean the giraffe skeleton. But other animals are much quicker. It depends on their size and the activity level of the beetles, which ebbs and flows with the seasons. In the summer, a racoon can be cleaned in less than a week. Bats only take a day or so. John’s work schedule is determined by the appetites of the beetles and the specimens being cleaned. It’s a non-stop balancing act.

John doesn’t think of the dermestarium as macabre or creepy. The work done there is a normal part of biological research. There are dermestaria and biology museums at universities across the country. And there’s a lot more to John’s job than just making sure the specimens are clean. For one thing, he’s got to think about what to preserve. How many bats are needed? How many giraffes? What species will be valuable to future researchers? This means he must keep up with the latest research, interact with colleagues and participate in professional societies.

Our tour ends and I depart through the dark tunnel, letting John get on with his work. After leaving, I realize I forgot to ask him if the turtle – or any of the other animals for that matter – has a name.

Next week: The magnetic observatory.

Sources:

[1] The Dermestarium, UW Zoological Museum, UW-Madison https://uwzm.integrativebiology.wisc.edu/dermestarium/

[2] Pliesch, UW-Madison and the Chamber of Flesh-Eating Beetles, UW-Madison Department of Entomology https://insectlab.russell.wisc.edu/2022/02/27/uw-madison-and-the-chamber-of-flesh-eating-beetles/

[3] Is it true that UW–Madison has a creepy-crawly underground chamber? Ask Flamingle, Wisconsin Alumni Association https://uwalumni.com/news/ask-abe-creepy-crawly/

[4] Schmitt, Preston, UW Mysteries, Secrets, and Hidden Places, OnWisconsin, May 28, 2022 https://onwisconsin.uwalumni.com/uw-mysteries-secrets-and-hidden-places/

[5] Carney, Marigrace, Flesh eating beetles gnaw creatures to the bone under Bascom, The Badger Herald, Oct. 30, 2014 https://badgerherald.com/news/campus/2014/10/30/flesh-eating-beetles-gnaw-creatures-to-the-bone-under-bascom/

[6] UW Zoological Museum, UW-College of Letters and Science https://uwzm.integrativebiology.wisc.edu/