This is the second part of a series on the shooting of Charles Arndt by James Vineyard in the Wisconsin Capitol in Madison. For part one, see Oddsconsin 55.

The shooting took place in the third Wisconsin Capitol, the first one built in Madison. The first capitol was established in a small wood-frame building in Belmont (Lafayette County) in 1836, before Wisconsin was a state. Burlington, Iowa, was home to the second capitol (also a small building) from 1837-38. After the building burned down, and with the creation of Iowa Territory in 1838, the seat of government moved to Madison. [1]

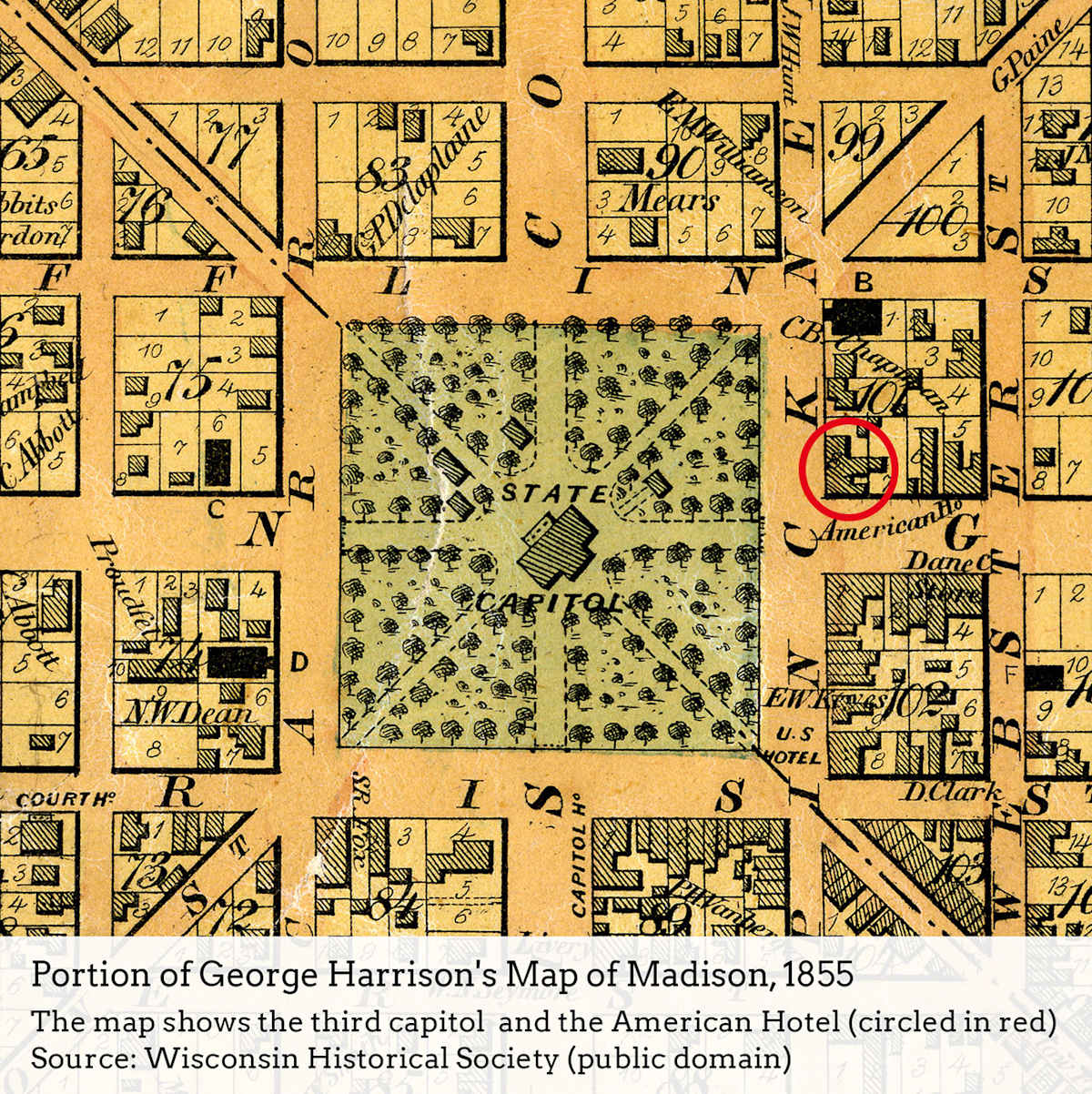

The third Wisconsin Capitol was built between 1837 and 1848 and sat at the same location as the current Capitol. [2] While the building was under construction, some meetings were held at the American Hotel (also known as the American House Hotel) on the corner of Pinckney Street and Washington Avenue. [3] Some delegates – including Vineyard – also resided at the hotel, which had eight tiny bedrooms and spaces in the attic “marked off by cracks in the floor.” [4]

The case against Vineyard took two years to go to trial, thanks to the legal maneuvers of Vineyard’s attorneys, one of whom was Secretary of Wisconsin Territory Alexander P. Field, who continued to hold this office through the events. Surprisingly, the Grand Jury in Dane County returned a charge of manslaughter, not murder, and then a change of venue to Green County was granted in 1843. At the trial, a verdict of not guilty was arrived at in a matter of minutes. [5][6]

After being acquitted, Vineyard served in the first Wisconsin Constitutional Convention of 1846 and was elected to the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1848. He later moved to California where he was elected to the California State Assembly and then the State Senate. [7]

Charles Dickens – the English Victorian-era author of A Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist and other classics – discussed the Arndt-Vineyard incident in his book, American Notes, which documented his travels in the United States in 1842. He included it in a chapter on slavery. He noted that while the killing did not occur in territory where slavery was legal, there was a “just presumption that the character of the parties concerned was formed in slave districts, and brutalised by slave customs.” [8]

After reviewing some additional examples of murders in other parts of the country, Dickens concluded,

Do we not know that the worst deformity and ugliness of slavery are at once the cause and the effect of the reckless license taken by these freeborn outlaws? … Do we not know that as he is a coward in his domestic life, stalking among his shrinking men and women slaves armed with his heavy whip, so he will be a coward out of doors, and carrying cowards’ weapons hidden in his breast, will shoot men down and stab them when he quarrels…in the legislative halls, and in the counting-house, and on the marketplace, and in all the elsewhere peaceful pursuits of life… [8]

The Arndt killing stirred emotions in Wisconsin. The practice of secretly carrying weapons into the council chamber was denounced, and the fact that Vineyard was released on bail immediately after he shot Arndt was met with disbelief.

One possible explanation for Vineyard’s lenient treatment is that, in the 1840s, it was not uncommon for “gentlemen” to settle their disputes with violence. Duels were a way of restoring honor that had been besmirched. In the United States, duels occurred well into the nineteenth century and involved senators, congressmen, cabinet members, governors, military officers, attorneys, physicians, judges, newspaper editors and others.

In 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr killed former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Burr served out his term as Vice President and, while charged with murder, was never tried for the crime. Andrew Jackson, before becoming president in 1829, killed a man in a duel, but was never prosecuted. Such is the elite privilege that was afforded the well-connected at the time.

Vineyard’s lenient treatment may also be explained by the actions of his powerful friends. For example, the law allowing a change of venue in criminal trials – which Vineyard’s lawyers relied on – did not exist until 1843, a year after the killing. There is some evidence that Vineyard pressured his colleagues in the Territorial Council to pass the law. On the other hand, it’s possible that Vineyard's lawyers merely took advantage of the territory’s “slipshod system of administering justice.” [6]

The Vineyard case became an issue at the time of John McCaffray’s execution in 1842. (See Oddsconsin 55.) To many, it seemed obvious that there were two systems of justice, one for the powerfully connected and another for everyone else. The differing fates of the two men showed that Wisconsin’s criminal justice system was biased and helped usher in the 1853 law that ended the death penalty in the state. [5]

Want Oddsconsin delivered right to your inbox? Subscribe here.

Sources and Notes

[1] Wisconsin Historical Society, Wisconsin Capitols. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2903

[2] The third capitol was replaced by a larger one, built between 1858 and 1869. This building suffered a severe fire in 1904, leading to the construction of the current, fifth, capitol.

[3] The American Hotel burned down in 1868. A plaque on the American Exchange Bank Building, which sits at the location of the former hotel, documents its role in Madison’s early days as the capital of Wisconsin Territory. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=36662

[4] The Historical Marker Database, American House. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=36662

[5] Daniel Belczak, Blood for Blood Must Fall: Capital Punishment, Imprisonment, and Criminal Law Reform in Antebellum Wisconsin. PhD Dissertation, Department of History, Case Western Reserve University, 2021.

[6] Milo M. Quaife, Wisconsin’s Saddest Tragedy, The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 5, 1921-1922, pp. 264-83.

[7] Find a Grave, James Russell Vineyard. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/197008840/james-russell-vineyard

[8] Charles Dickens, American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy. London: Chapman & Hall, 1913 edition. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/675/675-h/675-h.htm