There’s a fire in the boiler and she’s gonna blow

We’ve all got a ticket to the midnight show

- Kerry Livgren, Fire in the Boiler, 2022

This is the third and final post on Wisconsin Maritime disasters. [Post 1] [Post 2]

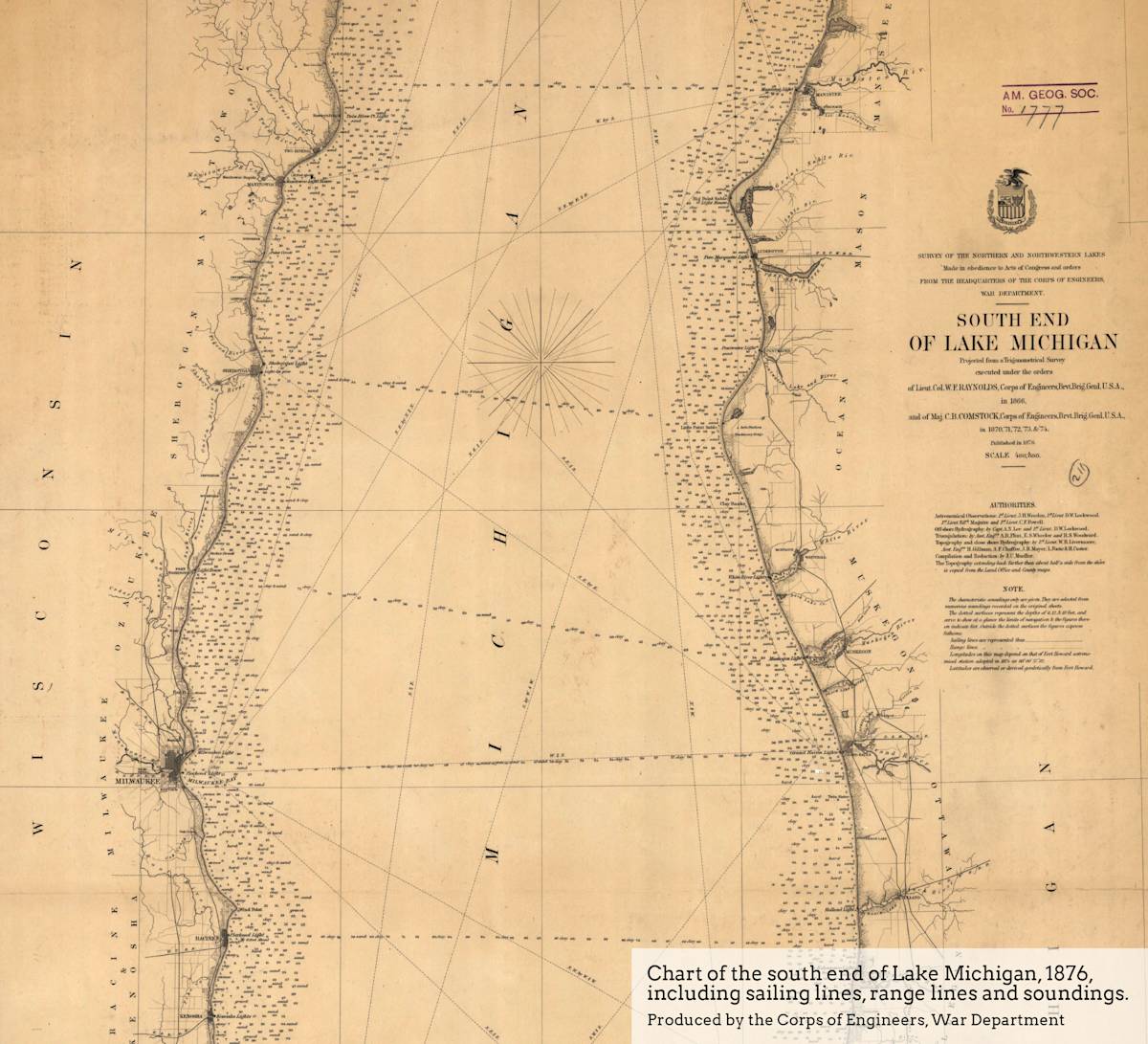

Despite the widespread fame of the Edmund Fitzgerald, Wisconsin’s deadliest maritime disasters didn’t happen on Lake Superior and didn’t involve big freighters carrying iron ore. They occurred on Lake Michigan, close to the Wisconsin shoreline, and involved steam-powered passenger ships.

Steam-powered ships – or steamers – first appeared on the Great Lakes in the early nineteenth century. They were considered technological marvels, as they were the first ships not powered by wind or human action. When the steamer Walk-on-the-Water appeared on Lake Erie in 1818, residents of Cleveland crowded the shore to get a look at the strange new vessel that belched a black cloud from its smokestack. [1]

The Walk-on-the-Water was a typical paddle steamer of the day, with paddlewheels on each side and two masts in case of engine failure. It plied the Great Lakes, carrying both cargo and passengers. It was powered by a steam engine, consisting of a large copper boiler and a single metal cylinder with a piston that drove the crankshaft. The water in the boiler was heated by burning cordwood, which generated steam to move the piston.

It wasn’t long before the inevitable occurred. The first steamboat explosion on the American side of the Great Lakes occurred in 1830, when the boilers of the Peacock erupted soon after the ship departed from Buffalo. Fifteen people lost their lives, most of them immigrants from Europe. [2] Many other steamship explosions followed.

The worst maritime disaster in US history was the result of a steam boiler explosion. In April 1865, the Sultana, a paddle steamer, was moving slowly up the Mississippi River, over-crowded with almost 2,000 Union soldiers returning north from Confederate POW camps at the end of the Civil War. On the night of April 27, just north of Memphis, the Sultana’s boilers violently exploded. The blast crippled the ship and set it on fire. Despite rescue attempts, over 1,000 (perhaps as many as 1,500) soldiers perished, along with crew members and other passengers.

Why do steam boilers explode? The causes are many – corrosion, sedimentation, defective construction, blisters, cracks, low water, improper maintenance, faulty repairs, carelessness and pressure overloading, to name just a few. The force of an exploding boiler comes from the super-heated water it holds under pressure. If the pressure boundary ruptures, the stored heat of the water is suddenly released. As the water vaporizes, its volume expands by a factor of 1,700 almost instantly. The boiler turns into a bomb. [3]

During the nineteenth and well into the twentieth centuries, boiler explosions occurred at an alarming frequency on steamships and railway locomotives. Also affected were almost every type of building – schools, apartments, machine shops, sawmills, breweries, textile mills, factories... The Grover Shoe Factory explosion in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1905 destroyed the four-story stone factory and left 35 people dead. Then boiler, 17 feet in length, shot through the roof of the factory and landed on a nearby home.

Boilers also caused fires when they overheated, the water level dropped to low, or burning wood or coal embers ignited flammable materials onboard. Fire was a killer on ships since means of escape was limited. Here the story turns to two of Wisconsin’s worst maritime disasters, the Niagara and the Phoenix.

The Niagara was a wooden paddle steamer built in 1845. With a length of 245 feet, a top speed of 15 miles per hour and luxurious accommodations, it was a “palace steamer” – a term used to describe the finest class of lake steamers in the era.

On its final voyage in 1856, the Niagara was en route from New York to Chicago with about 300 passengers. On the afternoon of September 23, the Niagara left Sheboygan for Port Washington. Five miles offshore, fire broke out and soon engulfed the ship. The few lifeboats available were overcrowded and some overturned. Some passengers clung to pieces of wood from the ship that were floating in the icy water. Since accurate records were not kept, the exact death toll is unknown, but was probably somewhere between 60 and 140. The cause of the fire was also never determined.

There’s a memorial in Harrington Beach State Park to the disaster. [4] The wreck sits in 55 feet of water east of Harrington Brach State Park in Ozaukee County. [5]

The Phoenix tragedy was even worse. The Pheonix was also a wooden steamer built in 1845, but it had a propeller rather than paddlewheels. On its final voyage in November 1847, the ship was en route from Buffalo to Sheboygan. Onboard were as many as 300 passengers (estimates vary), mostly immigrants from Holland planning to settle in Wisconsin. After making a stop at Manitowoc to replenish its supply of cordwood, the ship set out for Sheboygan on November 21. Seven miles from the city, fire broke out in the engine room and soon engulfed the ship. With only three lifeboats available, only about 45 passengers were saved and at least 190 people perished in the flames or the frigid waters of Lake Michigan.

The ship burned to the waterline and was later towed to Sheboygan harbor, where it sank. The wreck is visible today under eight feet of water near the Sheboygan City boat ramp. [6] There are several monuments in Sheboygan marking the tragedy, one in North Point Park [7] and the other in Deland Park. [8] The cause of the fire is thought to be overheated boilers, which set the wooden ship on fire.

Lake Michigan may seem charming at times, but it’s also home to the two worst maritime disasters (in terms of lives lost) on the Great Lakes. Both occurred south of the Illinois-Wisconsin state line. At the top of the list is the Eastland, which capsized in Chicago Harbor in 1915, taking 835 lives. Next is the Lady Elgin in 1860, the victim of a collision with another ship east of Highland Park, Illinois. The accident took almost 300 lives.

The list goes on and on. It gets to be a bit much, all of the death and destruction. It’s an important history lesson, but at a certain point, the death figures start to obscure the depth of the human tragedy. The accidents become statistics that are hard to relate to on a personal level. It’s difficult to imagine what the ships’ passengers or their families experienced. No one alive today has ever witnessed maritime disasters of these proportions on the Great Lakes.

Sources:

[1] William Ratigan, Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1977, p. 183.

[2] Ratigan, p. 186.

[3] Howard Veregin, Dog 137. Main Street Rag Publishing Company.

[4] Historical Marker Database, The Steamer Niagara: The Fiery End. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=47081

[5] Wisconsin Shipwrecks, Niagara (1845). https://www.wisconsinshipwrecks.org/Vessel/Details/455?region=MidLakeMichigan

[6] Wisconsin Shipwrecks, Phoenix (1845). https://www.wisconsinshipwrecks.org/Vessel/Details/505?region=MidLakeMichigan

[7] Historical Marker Database, The Phoenix Tragedy. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=32231

[8] Historical Marker Database, Fiery Passage. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=41888