The term “continental divide” conjures up images of a ragged line on a map, running down the spine of the Rocky Mountains. But Wisconsin has its own continental divide, near the city of Portage, where a narrow strip of land separates the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers. Water in the Fox flows north into the Great Lakes and then into the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River. The Wisconsin River runs west into the Mississippi, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico (now known officially in the US as the Gulf of America).

The Portage Canal, constructed in stages during the 19th century, crosses this divide and connects the two river systems. Only two miles in length, the canal ultimately became part of a 250-mile waterway – completed in 1876 – between Prairie du Chien on the Mississippi and Green Bay on Lake Michigan, with a series of locks at Menasha, Appleton, Kaukauna and other locations.

Portage is a French word meaning a place where a boat is carried overground. The name reflects the history of French exploration and fur trading in the area for several centuries before it became an American possession. Long before the French, the portaging trail known as Wawa’ąįja (pronounced wau-wau-ainja) was used by the Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk) people, whose traditional lands extend through parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri and Illinois. The Hoocąk are one of eleven federally recognized Native American nations in Wisconsin.

Early attempts to build the Portage Canal were haphazard. (For a detailed account see the National Register of Historic Places nomination. In 1835, the Portage Canal Company managed to dig a ditch large enough for a canoe. Further public and private ventures eventually succeeded in widening the canal so that, by 1856, it was large enough to accommodate a small steamboat. But it was not until 1876, several years after the canal was taken over by the US Army Corps of Engineers, that it became large enough for commercial boat traffic.

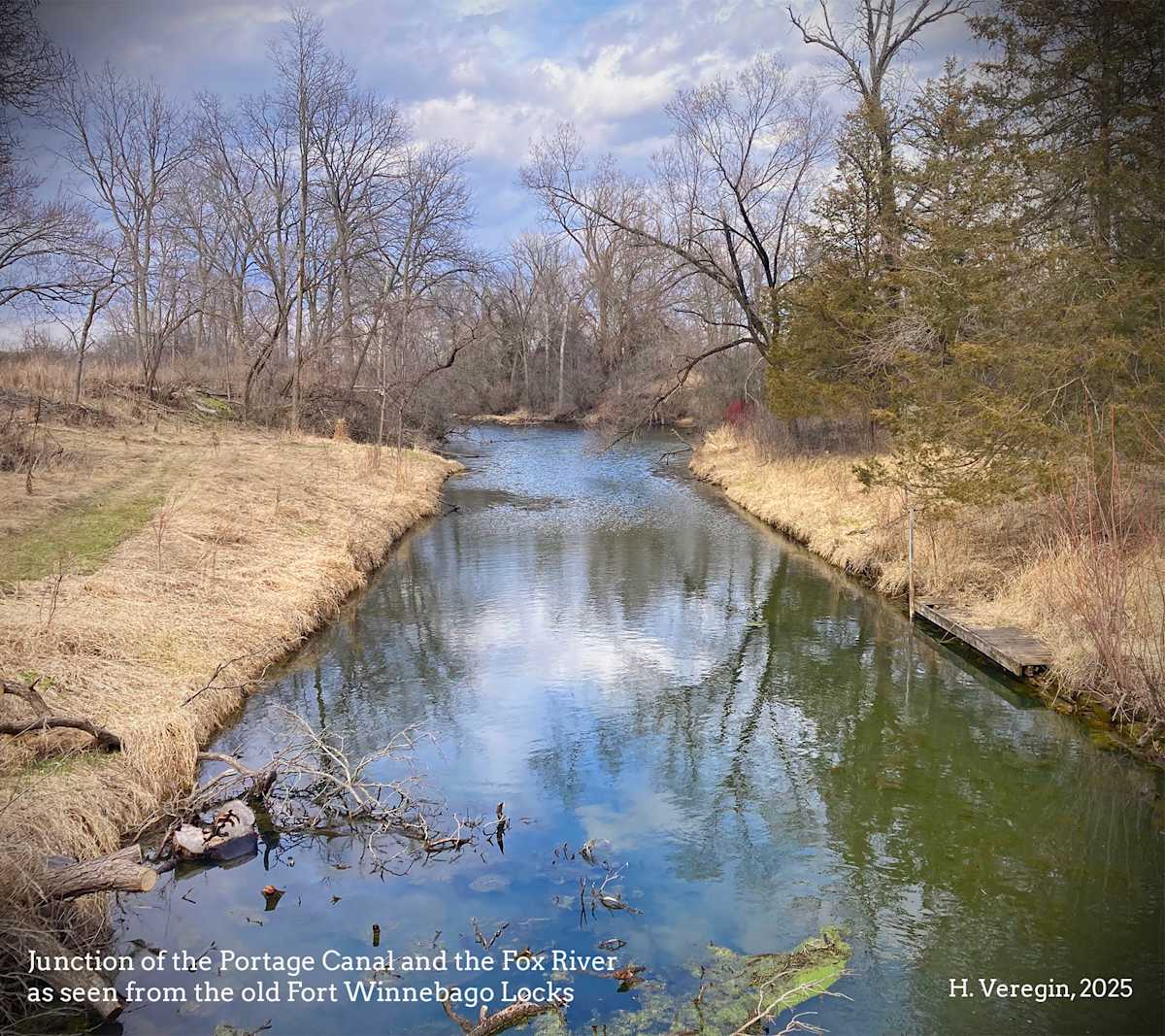

Two sets of locks were built, one near the Wisconsin River (Portage Locks) and one near the Fox River (Fort Winnebago Locks). The Portage Locks were first constructed in 1851 and rebuilt as a lift lock by the Corps in 1893. The locks have been inoperable since 1951, when the canal was decommissioned. South of the locks, the canal has been filled in and no longer reaches the Wisconsin River.

The Fort Winnebago Locks were built in 1859 and upgraded several times. They were destroyed when the canal was decommissioned in 1951. Only stone rubble and remnants of some revetments remain. These locks were named after Fort Winnebago, constructed on the north side of the Fox River by the US government in 1828. The fort was established to control the portage and support the government’s efforts to protect American settlers.

The establishment of the fort coincides with the beginning of formal surveying of the state to demarcate plots of land that could be sold to private citizens. (See Oddsconsin #12.) While Native Americans had been in contact with Europeans for centuries by this time, there had been no systematic effort to expropriate Native lands. The relationship was based instead on the fur trade. French and Native American cultures to some extent intermingled and intermarried. This changed in 1830 with the Indian Removal Act, which led to the forced removal of indigenous people onto reservations west of the Mississippi.

Fort Winnebago was part of the military infrastructure the government used to enforce these policies. A restored Indian Agency House, once the embassy for the US government and the Hoocąk Nation, sits near the remains of the Fort Winnebago Locks. A new historic display – called Walking Wawa’ąįja – tells the story of the government’s repeated attempts to expel the Hoocąk, their forced removal to distant reservations, and their determined efforts to return. Today, the Hoocąk do not have a traditional reservation in the state, but do own land in many Wisconsin counties.

The Portage Canal may have bridged the divide between the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers, but as a physical route for the expulsion of the Hoocąk, it is also a symbol of another kind of divide – one between the US government and Native American nations during the period of westward expansion.

Today, the Portage Canal is in disrepair, filled with aquatic vegetation and far too narrow for the steamboats that made use of it one hundred and fifty years ago. The canal never became the commercial success its builders hoped for. Like other canals of this era, it was quickly supplanted by the railroad – a reminder of the significance of transportation technology in shaping the cultural landscape of Wisconsin.

Sources: Historic plaques placed by the Portage Area Trails Heritage System; Historic plaques placed by the Portage Historic Preservation Commission, Portage Canal Society, Portage Area Chamber of Commerce, Portage Tourism Committee and Portage Parks & Recreation; Walking Wawa’ąįja historic display; Wisconsin Historical Society; Ho-Chunk Nation; National Register of Historic Places