The old Bayfield County courthouse in the city of Bayfield – now home to the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Center – has an interesting and unexpected history. A series of photos hanging on the walls of the first floor tells the story.

The first picture shows the courthouse in 1888, a few years after construction. At this time, Bayfield was the county seat. The courthouse looks much the same today, except that the clock tower is now gone.

A second picture shows the courthouse after the county seat was moved to Washburn, twelve miles to the south, in 1892. A new courthouse was built there and the old courthouse in Bayfield was no longer needed by the county. It later held offices for civic government, was used by the school district and served as a community center and a venue for celebrations and public events.

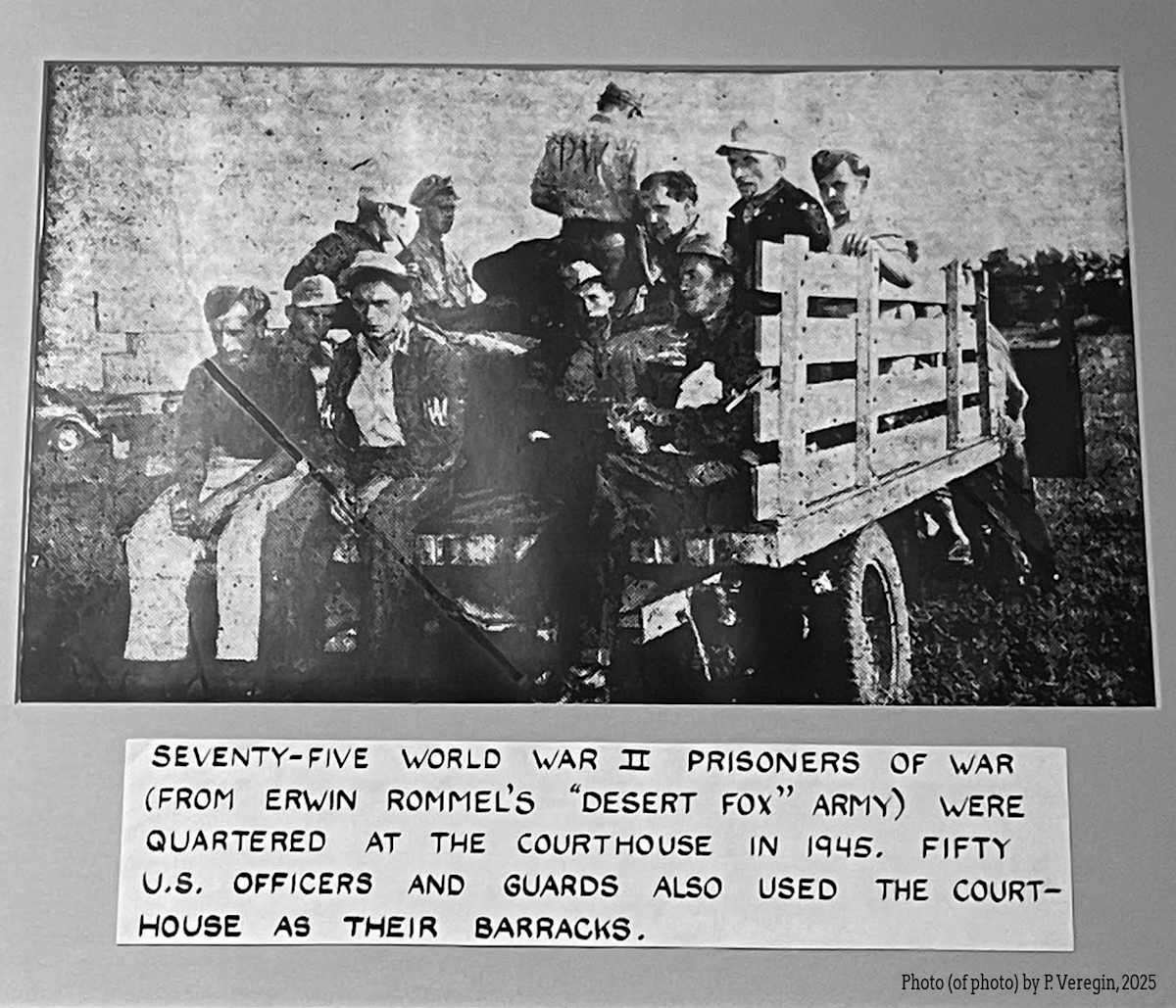

It’s the final photo that seems out of place. A group of young men – about a dozen – are seated in the back of a farm truck. They all look a bit dejected. One of the men is standing, his back turned to the camera. The letters “PW” are stenciled on the back of his shirt.

The men are World War II Prisoners of War (PWs or POWs) who were quartered in the courthouse in 1945. There were seventy-five POWs along with fifty US officers and guards.

It’s not widely known that POWs were held in numerous camps around Wisconsin during World War II. In her book, Stalag Wisconsin, Betty Cowley states that about 20,000 POWs were imprisoned in Wisconsin during the war. [1] Camp McCoy (now Fort McCoy) in Monroe County held 3,500 POWs from Japan, Korea and other Asian countries and 5,000 from Germany. [1] But many other prisoners were scattered around the state in branch camps, like Bayfield’s old courthouse. Cowley details thirty-eight branch camps in Wisconsin, spread over 25 counties. [2]

The branch camps were often temporary. At some, POWs were housed in tents or barns. Few of the camps have survived, one exception being the old Bayfield courthouse. There was also a seasonal ebb and flow, because the branch camps were in fact agricultural labor camps, organized to help Wisconsin farmers deal with the labor shortage caused by the war. The prisoners worked alongside local residents, picking and processing crops, tending to nurseries and dairies, or working in canning factories.

Prisoners were paid 80 cents per day and could establish an account for their savings, which were theirs after the war ended and they were repatriated. The system also put a lot of money into the US treasury, since the government kept the difference between what the POWs got and the prevailing wage that farmers or factories paid. [1]

Like many German POWs in Wisconsin, the prisoners at the old Bayfield courthouse were from General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. Rommel’s army was in North Africa to support Italy, an ally of Germany. The 1942 British/American North Africa campaign knocked Rommel out of the war and netted some 250,000 German and Italian prisoners.

Prior to the campaign, Britain and the US had been at odds about the US’s refusal to take POWs. But with so many prisoners, the British camps were overrun and the US had little choice but to consent. The US military eventually designated 156 POW base camps in nearly every state, where over 375,000 German POWs were eventually interned. [3]

The Bayfield camp was active during the summer of 1945, by which time the war with Germany was officially over. The POWs bided their time while the repatriation process worked through the system. Wisconsin farmers lobbied to keep the POWs around as long as possible, to help with the fall harvest. The prisoners picked beans, apples and berries in twelve-hour shifts, and worked at fruit-processing plants around the clock. [1]

The Bayfield POWs slept on the second floor of the courthouse, in the basketball gym. The building also housed guards, a kitchen, a mess hall and bathroom facilities. Tents were set up outside to house the overflow. A snow fence surrounded the back of the courthouse to keep curious citizens away. Two guard stations were also built, but by all accounts, security was quite relaxed, and no one really thought the prisoners would try to escape. [1]

The recollections included in Stalag Wisconsin speak about fraternization between the POWs and local citizens. Some stories tell of farmers taking their German POW crews to the local diner for lunch and even sometimes buying them beer. Given the state’s German-immigrant population, some residents no doubt had family or friends still in Germany, fighting in Hitler’s army.

History holds some unexpected secrets. The old Bayfield courthouse proves that, even eighty years ago in a supposedly simpler time, a complex web of global interconnections existed, linking Wisconsin farmers and residents to momentous events unfolding in Nazi Germany and North Africa.

Want to be the first to hear about Oddsconsin posts? Sign up to the email list here.

Sources and Notes:

[1] Betty Cowley, Stalag Wisconsin, Badger Books, 2002.

[2] The list includes Barron, Bayfield, Calumet, Columbia, Dodge, Door, Eau Claire, Fond du Lac, Green Lake, Iowa, Jefferson, Langlade, Milwaukee, Oneida, Outagamie, Ozaukee, Polk, Racine, Rock, Sauk, Sheboygan, Trempealeau, Washington, Waukesha and Wood counties.

[3] Kelsey Kramer McGinnis, A Captive (Enemy) Audience: Music and the Reeducation of German POWs in the United States During WWII, PhD dissertation, University of Iowa, 2020. https://iro.uiowa.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/A-Captive-Enemy-Audience-Music-and/9983968393702771